DAOs: Stakeholders, Autonomy, and Organisational Design

Understanding the issues with the D, A, and O in DAO.

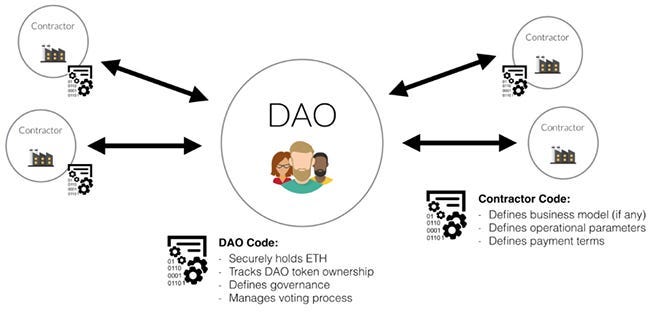

DAOs enable collective decision making on a global scale. It is designed to be publicly verifiable and offer transparency in real-time. These systems enable participants not only to coordinate decisions, but also to autonomously enforce them through on-chain execution.

At the heart of every DAO: a list of voters, a distribution of voting power, a voting system to tally the votes and a means to execute the will of voters.

People deploy DAOs to coordinate around a shared purpose. They can organise ad-hoc efforts like purchasing a copy of the US constitution, coordinate the treasury and decisions made by investor syndicates, or govern an entire ecosystem from the software to the organisational structure.

Let’s take this opportunity to explore the D, A, and O in DAO to better understand the principles behind it.

“D” in DAO — Targeting Stakeholders

A fundamental problem to solve in governance, regardless of DAOs or traditional systems, is distributing power to the right people. Those who are aligned with the mission, care about the system, and have meaningful skin-in-the-game for its long-term success.

This should happen naturally.

In corporate governance, a founder typically starts out with 100% ownership in the venture. Over time, through hiring, fundraising, and strategic partnerships, they gradually distribute ownership and influence to others who become aligned with the broader mission. Eventually, a company may go public, allowing an even wider set of stakeholders to gain a degree of influence.

In Bitcoin’s early years, Satoshi Nakamoto held all meaningful authority. Even after stepping back, Satoshi retained enough legitimacy to appoint a successor by naming Gavin Andresen as the lead maintainer. Over time, the mechanism of rough consensus took hold, and the Bitcoin Core project collectively established their own governance norms, determining who should have commit access and the ambiguous (alongside notoriously difficult) process for upgrading the network.

In the DAO world, the path of least resistance for distributing power is to issue a governance token. This is typical of DAOs that govern entire ecosystems. The intention is to allocate tokens to individuals aligned with the mission and motivated to participate from the outset.

Tokens may be distributed through mechanisms such as private fundraising, initial coin offerings (ICOs), and airdrops. In some cases, tokens are directly allocated to specific stakeholders, such as in proof-of-personhood systems or DAOs with defined membership, like an angel syndicate.

Depending on whether membership of the DAO is permissionless or restricted, tokens can also be made publicly available for others to acquire which allows them to gain alignment and the right to influence the decision making process.

Tokenisation lets us define voter eligibility based on ownership and typically compute voting power proportionally to token holdings. Many DAOs also support delegation which allows passive holders to outsource their votes to more engaged or knowledgeable participants.

To date, even if tokens are well-distributed, there is no guarantee that the people who should participate actually do. And sometimes, ideological proponents of public governance, actively discourage them from doing so.

For example, when a16z — Uniswap’s largest backer — votes against a proposal, it triggers backlash that a16z controls the Uniswap DAO.

This framing is misguided.

The voting system is working as intended.

Fairness is defined as voting power aligning with token ownership. The real issue isn’t that a16z can sway the outcome of a vote, it is that more large holders do not participate. Rather than discouraging major stakeholders from participating in the name of decentralisation, we should focus on encouraging broader participation across the board.

To summarise, the fundamental problem facing the D in DAO is ensuring the right stakeholders are actively participating in governance.

“A” in DAO — Autonomous and Control

The “A” in DAO — Autonomous — refers to the ease with which a DAO can exercise its authority and enforce outcomes based on decisions made by voters.

As we discussed previously, DAOs are typically deployed to govern a suite of smart contracts. This includes upgrading the smart contract code or invoking functions in the smart contracts to perform certain actions. For example, spending from the treasury, changing a configuration, or replacing privileged actors in the system.

The first example was TheDAO which launched in 2016. It was designed to serve as a decentralised governing body for a shared treasury. Token holders were expected to collectively review proposals and decide whether capital should be allocated. If the investments were successful, the returns could flow back to TheDAO’s token holders.

TheDAO raised 11.5 million ETH — roughly 15% of all ETH in circulation at the time — valued between $50 million to $150 million depending on the ETH price.

As history remembers, TheDAO ultimately blew up due to a reentrancy bug, but the concept has only grown stronger since.

Today, several major DAOs — including ENS, Arbitrum, Lido, Maker, AAVE — continue to pursue this original vision of decentralised governance. In fact, according to DeepDAO, DAOs across the ecosystem collectively manage approximately $15bn in assets. The autonomous aspect of a DAO in relation to governing smart contracts works as intended.

Of course, the story of autonomy does not end with smart contracts.

DAOs are no longer limited to controlling code. They are increasingly asserting authority over organisational hierarchies and even legal entities. To support this broader scope, new entities — often referred to as BORG-style entities — have emerged. These include efforts like Wyoming DAO LLC which attempt to provide legal clarity by recognising DAO votes as binding within a formal legal framework.

Unlike smart contracts, where control and authority are transparent and verifiable on-chain, applying the same level of clarity to the legal domain is more complex. It will take much longer for courts and legal systems to fully recognise DAO autonomy over real-world entities. It is not just about defining and structuring control, but that control being recognised and enforceable in legal adjudication.

“O” in DAO - Hierarchy via Popular Vote

A DAO is fundamentally a voting system that can govern a treasury that can be used to fund an organisational hierarchy.

Anyone can submit a proposal to:

Hire individuals or a team,

Form a committee,

Onboard service providers,

Form a new legal entity.

Voters are expected to review proposals, provide feedback, and cast a vote with their final decision.

This leads to a core, and often debated, principle of DAOs:

A community-wide vote must approve the compensation for a contributor or service provider.

The real-world equivalent of this situation is gathering all the villagers to a town square, presenting a proposal for some work, and asking everyone to vote on whether it should move forward at the proposed cost.

Many proposals do succeed through this process, leading to the hiring of individuals, teams, or service providers. But most people quickly realise this isn’t an effective approach to evaluate proposals, negotiate terms, or hold proposal authors accountable over the long term.

It soon becomes clear that a more structured organisation is needed to operationalise the DAO.

A common solution is to form committees to support procurement and coordinate specific initiatives. Committees are a popular model because they often function as consultancy-style arrangements:

Contributors can retain their full-time job while earning compensation for their work in the DAO in a side-gig capacity.

Service providers can participate as committee members and add an additional revenue stream for their business.

This approach helps bootstrap the DAO’s operational ability with people who can be onboarded quickly and start contributing immediately. Additionally, it is a means to instantiate optimistic governance, where people can make certain decisions on behalf of the DAO, while the wider DAO retains its ability to recall them.

However, DAOs become over-reliant on committees. It is not uncommon to see more than ten committees, each focused on different initiatives, with their own custom processes and contact points.

This leads to a range of issues:

Recruitment problems. How to attract and onboard talented people beyond those who are willing to lurk a governance forum,

Activity gaps. Contributors with a full-time job will prioritise their duties over their DAO responsibilities,

Role confusion. Service providers who typically adhere to a fixed scope of work are now making strategic decisions,

Synchronisation issues. All committees have their own communication and information flows – leading to potential silos.

Loss of information. Knowledge related to the initiative may not be preserved due to the ad-hoc nature of its membership and the cost to retain information beyond a committee’s remit.

There is also a recurring social tension: the perception of grifting.

Some proposals are seen as overcharging the DAO for the services offered. There are certainly cases where this may be true, but I am cautious about making that judgement lightly. When everything is public and compensation is determined through a community-wide vote, we shouldn’t be surprised (or upset) as people navigate that system to find work. The nature of compensation is inherently subjective and it often becomes contentious when made public.

The main issue with the committee approach isn’t the structure, but the fact that membership is often by people scattered across the ecosystem and lacking a central touch point. People are willing, and want to get involved, but it is often lacking a core team or members who steward the committee’s direction.

With the above in mind, the next natural step in building a more structured organisation for the DAO is the creation of a legal entity:

Job security for contributors,

Hire full-time staff via a traditional recruitment process,

Synchronise team under a common leadership,

Negotiate terms with service providers.

This often leads to jokes that DAOs are simply relearning everything that led to theory on firms. It also invites criticism that the DAO’s organisational structure is becoming increasingly centralised and at odds with the original vision of decentralisation.

There might be some truth to these critiques, but we should recognise that every community has the right to organise itself according to its own needs and values.

Take Ethereum’s early evolution, for example: The Ethereum Foundation led protocol research, Consensys acted as a venture studio to incubate startups, and other companies like Parity played key roles in the ecosystem. It progressively decentralised across different companies and firms.

Every ecosystem is different.

The goal should be to organise in ways that solve the problem at hand and anchored in shared values, but not constrained by rigid ideology.

Summary

The easiest part of building a DAO is implementing the on-chain voting protocol and designing the membership token. These technical components are well understood and straightforward to deploy.

The hardest challenges, however, are fundamentally human. They involve ensuring that aligned stakeholders are actively participating, that contributors are organised in a way that supports the long-term success of the DAO, and that the DAO’s authority is respected in legal disputes across jurisdictions.

In many ways, DAOs serve as a microcosm of real-world organisational dynamics as it showcases how people coordinate, distribute power, and build institutions from the ground up. The progression from individuals to committees to fully formed legal entities often mirrors the very problems that gave rise to the theory of the firm.

Yet despite these parallels, DAOs introduce fundamentally different constraints. Their global reach and radical transparency creates unique challenges. Recruitment often occurs through public elections, negotiations play out in real-time and in full view of the public as proposals move through the governance process, and participants frequently weigh short-term incentives against long-term interests.

We explore these dynamics further in the next article — so dive in and learn more about DAO Politics: Holistic Challenges in the Proposal Process!