DAO Politics: Holistic Challenges in the Proposal Process

Where good intentions slow progress, vendors compete, and decisions get political

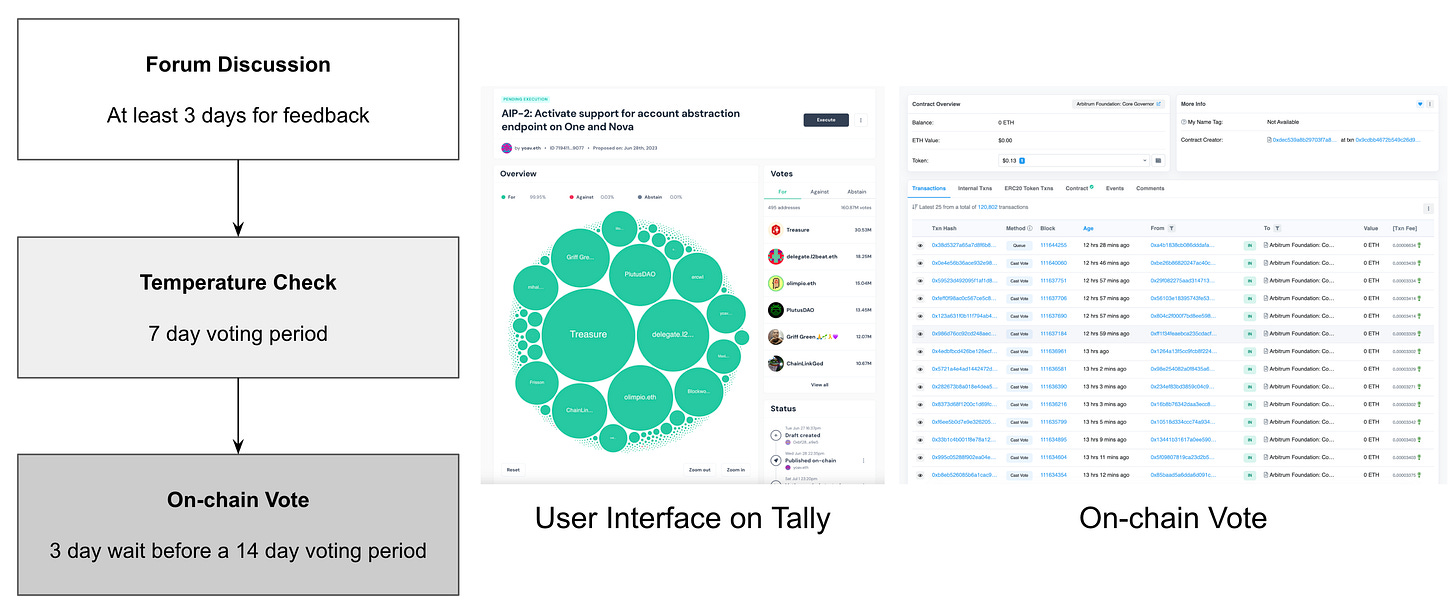

The heart of every DAO is a public proposal process which invites anyone to participate in, encourages negotiation, and a community-wide vote to decide whether a proposal should move forward.

We’ll explore several key issues that arise in the proposal process: lobbying and coercion, competitors and frameworks, rigid proposals that lead to inaction, and voter apathy driven by the sheer volume of proposals – all of which fall under what is often called “DAO politics”.

This is not an exhaustive list, but I believe understanding these challenges is essential before we can design solutions for more effective governance.

Navigating Proposal Process and Preference for Frameworks

While the proposal process can generate valuable ideas and attract contributors, its open and public nature also creates friction. As we will see, authors may face a swarm of competitors or opposition before their work can advance. At the same time, in order to appease all parties, DAOs will lean towards frameworks that share the work amongst everyone as opposed to making opinionated bets.

Navigating Among Too Many Chefs

A well-meaning proposal can attract tens or even hundreds of comments from delegates, each with their own suggestions, critiques, and conflicting priorities:

Delegates might question the scope,

“Why target this user group?”

Demand greater DAO participation,

Why not include other contributors?

Suggest entirely new directions.

Why not pivot the proposal and apply the same skills to a different problem?

The entire process can quickly become a minefield for the author to navigate and usually ends in one of three ways:

Navigated successfully. The author manages to navigate the politics involved in pushing a proposal through the DAO, it is approved by delegates, and they can then execute the work on behalf of the DAO.

Abandon proposal. An author may struggle to navigate the contradictory feedback and fail to gain a sense of whether delegates will support the proposal. It is not uncommon for the author to eventually abandon the proposal even if it is overall a good idea that is likely to pass.

Ultimatum dynamics. An author may reach a breaking point after attempting to negotiate with the host of delegates and simply offer an ultimatum: "either accept the proposal as-is or reject it”.

The fundamental issue is that a proposal author is forced to navigate a fragmented and often uncoordinated group of delegates rather than negotiating with a single counterparty.

Even if an author navigates the process successfully, it does not imply the final proposal is optimal for execution. A proposal that survives the process often undergoes significant revisions which can improve it, but also introduce compromises and complications that hinder its long-term success. In ultimatum cases, delegates may approve flawed or overpriced proposals simply to ensure there is progress in the DAO.

This dynamic becomes especially concerning when the DAO controls a large treasury. A single proposal that overcharges the DAO can easily be overlooked. Also, and potentially more concerning, delegates bear no direct costs to them and the impact on the DAO’s treasury as a whole appears negligible in the short term. If the problem is left unchecked, this pattern can lead to inefficient spending and accelerate the depletion of the treasury.

Competitors and Frameworks

The public forum, in some ways, serves as a natural discovery mechanism for identifying service providers interested in offering a particular solution.

For example, let’s assume a service provider publishes a proposal to the DAO that offers their services in exchange for a fee. A competitor sees the opportunity, quickly assembles a similar pitch, and submits a competing proposal. As a result, multiple proposals addressing the same problem often appear on the forum in quick succession.

On a positive side, this shows that service providers are actively engaging with DAOs and looking for opportunities. The DAO attracts interest without needing a formal request for proposals process as long as one service provider is willing to pull the trigger.

The downside is the swarm effect.

Once multiple competitors are involved, the path of least resistance often shifts from evaluating and selecting the best proposal to establishing a broader framework where all participants can benefit financially. Because this process unfolds in public, it also becomes socially difficult to reject some proposals outright, even when, in a traditional procurement setting, only a handful of providers might be chosen.

On top of all this, there is a prevailing ideology in DAOs that resources should be shared equally amongst all who apply. Swarms of competing vendors often reinforce this mindset as it increases their chance of inclusion. But this approach is problematic as resources, like funding and team capacity, are limited. It also encourages political maneuvering to appease everyone rather than focusing on solving the actual problem.

Lesson: True equality isn’t what most people really want. What they value more is fairness, the sense that everyone has a chance, outcomes are based on merit, and the rules apply equally to all.

Vendor Specific Proposals and Not Strategic Goals

It is common for proposals to be written in a way that only the author is positioned to carry out the work. From the author’s perspective, this is rational. Avoid competition, keep delegates focused, and present themselves as the only option.

Interestingly, at times, authors may even apply social and emotional pressure on delegates to justify the funding. After all, the author went through the effort to write the proposal, navigate the DAO’s proposal process, negotiated with all the delegates, so it should be funded.

In my view, it is problematic for the DAO to facilitate vendor-specific proposals. It prevents the DAO from running a more deliberate and competitive procurement process which not only helps find a good team, but also leads to competitive pricing to complete the job. Tying a proposal to a specific vendor also has a lock-in effect that makes it difficult to terminate the service as it often requires a community-wide vote and the public process that entails.

The final, and perhaps biggest issue, is that vendor-specific proposals put the DAO in a reactive position. Many delegates are still new to the reality that an avalanche of vendors want to sell their services. When a polished offer shows up, it feels novel and there is an instinct to make it work, even when the service is not necessary. There is still a large degree of innocence amongst the community on the persistent lobbying by vendors in order to win business deals.

Rigid Proposals, Accountability and Too Much Control

In practice, delegates are expected to track the progress of approved proposals and ensure that authors deliver on what was promised. Especially when those same authors return with follow-up proposals that request further funding to continue the work.

This brings up a broader challenge: accountability.

When reviewing a proposal, a delegate must assess not only how to improve the idea, but also how the author will be held accountable for delivering the final outcome.

In the simplest case:

Is there a clear and objective way to determine whether the proposal was successful?

To answer this, delegates will often request a list of ‘key performance indicators’ (KPIs) and/or ‘objectives and key results’ (OKRs) to help define what success looks like after the proposal is executed.

For example, if a proposal seeks funding to run an accelerator for 30 early-stage startups, a KPI might specify that at least five of those projects should graduate and go on to raise a Series A from top-tier venture capital firms.

In the harder case:

Did the author actually do what they said they would?

The question often leads to proposals resembling cooking recipes: a list of ingredients, set of instructions, and the final outcome. Proposals become rigid and authors are expected to follow the plan exactly as defined.

The motivation for delegates to advocate for a rigid structure is understandable. It makes it easier to estimate costs and verify whether the work was delivered as promised. However, the need for a rigid structure can backfire.

More often than not, authors will discover a better approach or want to course correct while executing the proposal, especially if any unforeseen circumstances materialise which happens quite often. However, any deviation from the approved plan typically requires a follow-up community-wide vote. This is a herculean effort in its own right and may delay the proposal’s execution by at least 2 weeks, if not months.

As a result, even when changes would clearly benefit all parties, authors often stick to the original plan simply because that is what was approved. The system rewards strict adherence over iterative improvements.

The fundamental problem is that the DAO proposal process follows a waterfall model when in reality most organisations may agree upon an initial plan, but follow an agile methodology to quickly iterate on the plan as new information becomes available.

Voter Apathy, Too Much Volume and Repetitive Work

One of the common mistakes DAOs make — like many new systems — is over optimising for participation. They design incentives to attract more contributors, more voters, more proposals, and aim for maximum engagement from everyone all the time.

But this overlooks a simple constraint: delegates have limited time.

In reality, most delegates can only meaningfully process a handful of proposals per month. Yet, when there are four or more proposals per week, each requiring time to read, understand, assess, and to vote on, it is no surprise that delegates are overwhelmed simply by volume alone.

Worse still, if multiple proposals are passed weekly, the DAO ends up with tens or even hundreds of active work streams running simultaneously. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing if the organisational structure exists to manage that level of throughput. But in most cases, it cannot. And work begins to fall through the cracks. Not because anyone is incompetent or avoiding work, but simply there isn't enough capacity to keep up.

When it comes to reviewing proposals, delegate incentive programs have appeared that financially compensate delegates to vote, leave comments, and engage publicly.

While some feedback is thoughtful and genuinely valuable — as the program intends — these incentives can also distort the conversation and encourage spam-like behaviour. In some cases, delegates leave superficial comments in order to tick the box required for rewards. Going further, some feedback even appears to be AI generated. Both contribute little to the actual discussion.

On the topic of feedback, public discourse is not ideal if a delegate wants to share criticism of the proposal. Even the slightest public criticism can damage the relationship between a delegate and a proposal author. As a result, delegates tend to offer feedback privately to avoid public shaming or reputational fallout. This creates a disconnect, where public discussion appears positive, while private sentiment among delegates may be far more critical.

This probably reveals a deeper truth that governance needs to adapt to how delegates prefer to give feedback, even if that doesn’t always happen through public discourse.

Social Pressure, Private Voting, and Delegate Transparency

DAO governance often involves tensions between authors of a proposal and delegates who vote on the proposal.

Proposal authors often lobby delegates to support their initiative. Because voting is public, delegates who oppose a proposal risk burning social capital, especially if they plan to bring forward their own proposal in the future.

Some degree of lobbying is healthy within a decision making framework and it should be encouraged. But problems arise when lobbying distorts incentives. If a coercer can force delegates to prioritise short-term relationships or their own reputation over long-term interests of the DAO, then it may result in non-optimal outcome and represent a potential takeover of governance.

Private voting can help mitigate this and reduce social pressure. Delegates can publicly commit to a position, but privately vote according to their own judgement. However, privacy only goes so far. If a coercer can observe the voter as they cast their vote or if a voter can prove how they voted afterwards, then the pressure may still remain.

Unfortunately, private voting introduces inherent trade-offs that make it difficult to adopt in DAOs.

One major issue is delegation. In most DAOs, token holders delegate their voting power to others. But if votes are private, delegators lose the ability to verify how their delegates voted and whether those votes align with their own preferences. Selective disclosures, where the voter can reveal their votes to delegators and not others, can help address this issue. But it comes with its own attack surfaces (e.g., poisoning attacks) and remains largely unexplored in the context of DAOs.

A second issue is autonomy. Most private voting systems rely on one or more external tallying authorities to complete the cryptographic tallying process and publish the final result. This is because a smart contract cannot securely hold or use private keys. Dependency on a tallying authority undermines the DAO’s autonomy. If the tallying authority goes offline, for whatever reason, then the voting process halts and the DAO loses the ability to guarantee liveness and enforce outcomes on-chain.

Summary

The proposal process invites public participation, negotiation, and relies on community-wide voting to make decisions. While the structure aims to be inclusive and transparent, it also introduces significant political, operational and social challenges often referred to as “DAO politics.”

This article examines key friction points that emerge within the process:

An overwhelming volume of proposals,

A minefield of contradictory feedback for authors,

Lobbying and social pressure on voters,

Swarm of competing vendors and vendor-driven proposals,

Rigid proposals that read like cooking recipes,

Private voting is difficult to implement and not a silver bullet.

In many cases, the frictions arise not because parties are malice, but because they are well-intentioned.

Proposal authors want to be fairly compensated for carrying out work for the DAO, vendors do not want to lose out to their competitors, voters want to ensure everyone is accountable to what they promise the DAO, and the transparent nature of the system encourages engagement from all parties including those who lack context but genuinely want to help out.

The voting infrastructure works as intended. The real challenge is human.

A core challenge is assigning trust and who can be relied upon to carry out the DAO’s will. When each proposal comes from a new, unvetted team, and voters must perform diligence every time, then it is no surprise that voters are overwhelmed, vendors flood the process, and authors face contradictory feedback.

To address this, DAOs need to establish a middle ground, where trusted teams or bodies are empowered to act on the DAO’s behalf. These entities can take responsibility for executing proposals, overseeing vendors including hiring and terminating them, and making decisions that are in alignment with the intention of an approved proposal.

By doing so, DAOs can move beyond rigid processes and towards more agile, accountable execution, without sacrificing the core value that is important: autonomy, control, and the supreme decision maker.

There are some solutions based on the above that we explore in the next article — Learning From Failures to Build Better DAOs.