From Credible Neutrality to Security-First Neutrality

Revisiting Credible Neutrality in the Age of Institutional Adoption

The promise of crypto lies in disintermediation, publicly verifiable systems, and credible neutrality — the foundations of an open economic system that is accessible to anyone regardless of geography, identity or beliefs.

Credible neutrality is one of the most important concepts in the industry and it took several years for the community to settle on a term that captures this ethos.

Vitalik has a rule of thumb for what it means:

Credible neutrality. Essentially, a mechanism is credibly neutral if just by looking at the mechanism’s design, it is easy to see that the mechanism does not discriminate for or against any specific people. The mechanism treats everyone fairly, to the extent that it’s possible to treat people fairly in a world where everyone’s capabilities and needs are so different.

Crucially, credibility matters as much as neutrality itself. A system must not only be neutral in design, but also provably so to its users. Neutrality must be backed by social legitimacy and a technical means to achieve it.

This essay will not argue that credible neutrality should be abandoned. Rather, we examine how practical security pressures are reshaping how neutrality may be implemented, especially for institutions who may adopt rollups as a technology stack.

Evolution of Credible Neutrality

The phrase, credible neutrality, originates from the Ethereum community and it is often applied retrospectively to Bitcoin.

Bitcoin laid much of the groundwork for what is now described as credible neutrality. It was the first to implement a set of publicly verifiable consensus rules that self-enforce the network’s integrity without a trusted third party or mediator.

Collectively, the network enforces:

The 21 million supply cap,

The issuance schedule for new bitcoins,

Rules governing transaction validity,

A total ordering of all confirmed transactions,

Going further, the chain advances through an open competition among miners to produce new blocks and the competition is based on solving computationally difficult puzzles. The only advantages available to a miner are network latency, hardware efficiency, capital investment to set up a mining farm, and the ongoing operational cost to run it. There is no discretionary authority who can bypass the competition.

Attempts to violate consensus rules such as including invalid transactions or producing blocks without participating in the competition are simply ignored by the network at large.

Equally important are the social foundations of neutrality.

Bitcoin’s founder Satoshi Nakamoto stepped away early in the project’s development. He left the community to steward the project’s future. The absence of a central authority has helped prevent coordination around discretionary rule changes. Any attempt to change the rules is often heavily scrutinised and must overcome the toxicity of Bitcoin maximalists who act as a ‘swarm of cyber hornets’.

Taken together, these technical and social dynamics help explain why Bitcoin is widely regarded as a credibly neutral system. To understand how neutrality manifests in practice, however, it is worth examining one of the most critical mechanisms: transaction ordering.

Transaction Ordering and the OP_RETURN Wars

This brings us to arguably one of the most important mechanisms underpinning credible neutrality in blockchain networks:

The transaction ordering policy and the question of ‘censorship’.

At first glance, Bitcoin is often assumed to embody strict neutrality. The common view is that all transactions are treated equally, so much so, that even sanctioned actors like North Korea prefer to keep their holdings in BTC over all other crypto assets.

Yet this assumption on neutrality is not necessarily true.

There is a long-running and ongoing conflict in the Bitcoin community called the OP_RETURN wars. The debate focuses on what type of data should be permitted within transaction payloads:

OP_RETURN. The signer can store arbitrary bytes in the transaction payload. The data must be sent alongside the transaction and the new block, but it is not kept in the network’s active state (UTXO set). It contributes toward the ~4 MB limit of a block.

The debate is nearly as old as Bitcoin itself, but in recent years, it has re-emerged due to the popularity of Ordinals and a single jpeg of a ‘bitcoin wizard’ filling an entire ~4MB block.

This raises the question on what it means for a transaction ordering policy to be credibly neutral. Historically, it has relied on the following rule of thumb:

Fee market neutrality. A transaction should be ordered for execution based solely on whether it pays a sufficient fee at the time of inclusion.

Practically, this means block builders evaluate whether the fee compensates for execution and block usage without judging the transaction’s content or intent.

The current debate is often framed as a divide between Bitcoin Core developers and the Knots community. Broadly speaking:

Bitcoin Core developers tend to favour allowing the fee market to regulate transaction content without explicit filtering mechanisms.

Knots proponents characterise OP_RETURN usage as spam that undermines node decentralisation and thus filtering can help preserve neutrality of value transfers into the long-term.

Regardless of where one stands, the dispute is fundamentally about credible neutrality:

Should any transaction be permitted as long as the sender is willing to pay the market price for blockspace?

Should the network prioritise financial transactions above all else and scrutinise the intent behind certain payloads?

The tension between relying on an open fee market to enforce neutrality or whether content filtering can be justified for the greater good is not only a debate in Bitcoin. As we will see, it is a prominent debate across the blockchain ecosystem more broadly.

Ethereum’s Credible Neutrality in the Face of OFAC Sanctions

Ethereum was born with a similar ethos to Bitcoin. It was envisioned to be a world computer running unstoppable code without central control.

Admittedly, there was a blip in Ethereum’s credible neutrality in the early days, as the community coordinated a hard fork to reverse the effects of TheDAO hack and return funds to affected participants. It is the only occasion where the community as a whole interfered with the system’s operation.

Over time, a stronger cultural norm emerged within the Ethereum community. Network rules should not be changed in response to a bug at the smart contract layer. Intervention by core developers is only appropriate for fundamental vulnerabilities in the blockchain protocol.

This cultural norm was first tested a year later with the Parity Wallet hack in 2017. More than 150k ETH was frozen due to devops199 exploiting a bug in the implementation of a multisig. Parity, at the time, was one of the two core development teams for Ethereum. The hack was not reversed, which upheld credible neutrality, but it was arguably one of several contributing factors that led to the departure of Parity as a core developer.

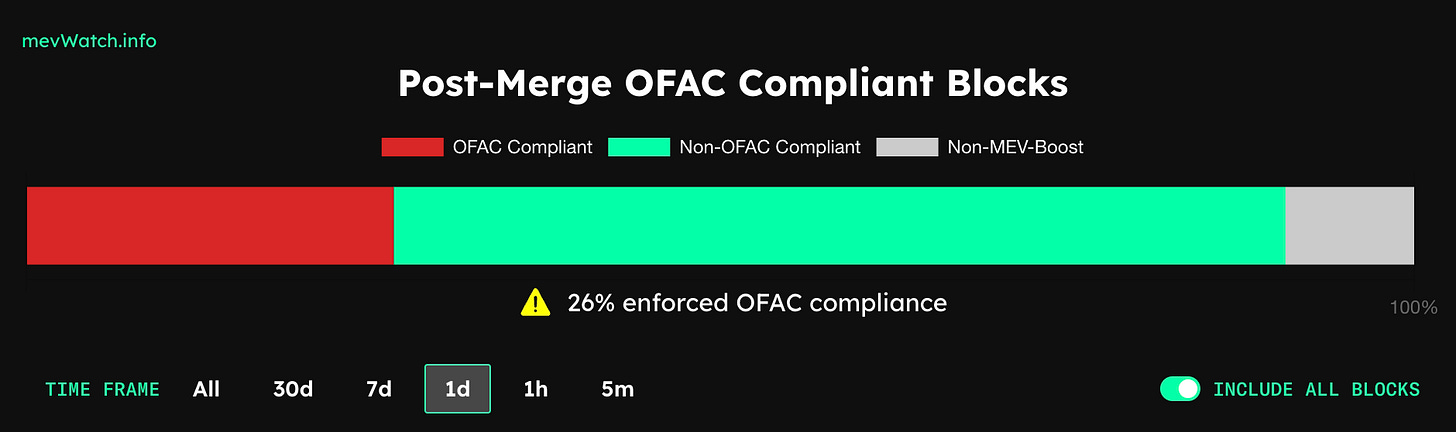

In my view, the real test of credible neutrality in Ethereum was the network’s response to the Tornado Cash sanctions. In a nutshell, the US Government sanctioned the Tornado cash smart contracts. This means anyone interacting with or facilitating transactions involving them could potentially face violations of US sanctions law and significant legal consequences.

Despite regulatory pressure, Ethereum’s proof of stake protocol did not censor transactions or alter the consensus rules, even though a majority of stakers and some infrastructure providers compiled with sanctions. The network continued to process Tornado Cash related transactions, albeit with a short delay.

Looking back, this was the right decision by the Ethereum community as a recent court ruling declared that an immutable smart contract may not qualify as sanctionable property and the sanction was later lifted by the US Government.

Rollups Pursue Ethereum’s Path

Rollups follow Ethereum’s path in embracing credible neutrality. Some argue that a centralised sequencer cannot be credibly neutral — a question we will return to shortly.

If we focus specifically on the sequencing layer, then the case for credible neutrality can be even stronger in some respects than Ethereum. A sequencer’s primary role is to collect transactions as data blobs, order them, and publish them to Ethereum. While sequencers typically verify transaction validity and confirm that signers can cover fees, even this is not strictly required at the protocol level.

In principle, a sequencer could publish all collected data blobs, including invalid transactions. The rollup smart contracts will simply ignore those that fail to execute. The trade-off is economic as the sequencer will bear the cost of posting invalid data without reimbursement.

A centralized sequencer or several acting in concert can censor transactions by withholding data publication. Many rollups mitigate this risk through an escape hatch mechanism that allows users to transact or withdraw funds if the system becomes unavailable. In practice, these mechanisms help preserve credible neutrality by enabling users to bypass the sequencer if their transactions are not included.

However, as we will see, the sequencer’s ability to withhold data and not order it for execution can shift systems away from strict credible neutrality towards discretionary security enforcement.

Emerging Trend To Pursue Security-First Neutrality over Credible Neutrality

We are increasingly witnessing a shift in the Overton window as some projects move away from strict adherence to credible neutrality and toward what might be described as security-first neutrality:

Security-first neutrality. Preserves the goal of impartial infrastructure, but prioritises protecting user funds when credible threats arise, even if that requires selective intervention.

There are several historical precedents which suggest that a security-first neutrality paradigm is often viewed as desirable by users and projects.

Ethereum’s response during TheDAO hack was the first instance of security-first neutrality. Other events include Binance halting their smart chain to reduce impact of a cross-bridge hack, Berachain’s emergency hard-fork to freeze hacker funds and SUI working with their validators to freeze hacker funds.

Additionally, there are proposals which have not been realised but reflect similar instincts. For example, Changpeng Zhao (CZ) once floated the idea of rolling back Bitcoin’s blockchain to rescue 7,000 BTC. Meanwhile, Optimism’s documentation presents an approach to fork Ethereum L1 and rescue funds in the event that Optimism’s core blockchain protocol was hacked.

Among these cases, a common theme emerges that developers may be forced to intervene if the hack represents an existential threat to the blockchain ecosystem at large.

Filtering Transactions At The Sequencing Layer

Returning to the issue of centralised sequencers and their ability to selectively withhold transaction data, there is a growing trend for a new category of infrastructure that focuses on security-first neutrality.

The new infrastructure empowers the sequencing layers to evaluate transactions for potential misuse before deciding whether to include them in the final ordering.

One early example is Flashbot’s revert protection. It simulates transactions before inclusion and will drop valid transactions that can pay a fee, but the execution has failed for any reason. The benefit is that users are no longer charged for failed transactions. A few years ago, revert protection was made available as an optional integration at the RPC layer but it can now be incorporated at the sequencing layer for rollups. It is interesting that Unichain offers revert protection, but it was not enabled on Base.

More recent offerings go beyond revert protection and focus explicitly on exploit prevention. This includes products like STOP by Blocksec, Forta Firewall by Forta, Hexagate by Chainalysis. They rely on machine learning and other techniques to flag whether a transaction is attempting to exploit a smart contract. Another startup, called Credible Layer by Phylax allows projects to explicitly define a list of invariants which is used by the sequencer to block any transactions that violate the invariants.

Transaction Filtering Is Not Free and Has Some Complications

The appeal for transaction filtering is clear from a security perspective. Early detection can slow or halt exploits, alert affected projects, and provide time to coordinate responses that protect user funds. Yet this capability also shifts sequencers closer to an intermediary with discretion rather than neutral ordering infrastructure.

However, transaction filtering is not without costs and complications:

Liability. Questions quickly arise around responsibility if filtering fails to stop an exploit. Does liability fall on the sequencer, the filtering provider, or neither if the service is framed as best-effort?

Facilitating upgrades. Many attacks can be addressed by projects updating their smart contracts. However, when mitigation requires upgrading the underlying blockchain itself, like replacing an immutable smart contract, the task can place significant pressure on core developers and the broader ecosystem who will need to update node software within a short period of time.

Bypassing filters. Attackers often test exploits on public (and private) testnets before deploying them on mainnet. If filtering APIs are accessible, adversaries may probe them with test transactions to learn what is blocked and how to work around its defences. Probes can provide APIs with useful information and notice of an upcoming attack, but distinguishing signal from noise, at scale, can be challenging.

Scope creep. What begins as narrowly defined exploit prevention can gradually expand. The narrative of protecting users may justify broader transaction screening, potentially moving from technical exploit detection toward behavioural or activity-based filtering, raising concerns on credible neutrality.

False-positives. No detection system is perfect. Legitimate transactions may be incorrectly flagged or delayed. In fast-moving DeFi environments, delays can have real financial consequences. For example, if a user is prevented from topping up their collateral before liquidation, then they’ll lose funds without any recourse.

Latency. Transaction simulation, analysis and filtering introduces additional processing overhead. As rollups and other blockchain networks push towards ever-lower latency transactions such as less than 100 ms, and hopefully 10 ms, then even a small increase due to filtering efforts will eventually become material and have an impact.

Appeals. In cases of false positives, users must identify the appropriate party and request that the transaction be unblocked. This may require additional human resources for the entities running the sequencing layer or alternatively force users to rely on the filtering provider to resolve the issue.

There are many cases where teams can remedy issues by updating smart contracts directly.

For other cases, where the core developers must be involved to update the core blockchain protocol, we need to consider proportionality. For example, it does not necessarily make sense for hundreds of infrastructure providers to upgrade node software to rescue funds from a smart contract holding less than $100k in TVL.

Unfortunately, this is the kind of judgement core developers may be forced to make if they are expected to intervene at the smart contract layer. While the promise of security-first neutrality may be appealing to users, its practical implementation can be challenging for core developers, particularly as ecosystems grow in scale and complexity.

An interesting research area is to evaluate all previous exploits and determine whether transaction filtering could have prevented it alongside the sequence of events needed to fix the exploit.

Institutions Will Adopt Security-First Neutrality

The Overton window is clearly shifting.

Credibly neutral base layers like Bitcoin and Ethereum will likely remain as foundational settlement infrastructure, but institutions adopting rollups as a technology stack may prioritise security-first neutrality for their own execution environments.

They will likely implement preventative security like transaction filters and reactionary security measures like security councils to recover funds (when possible). The motivations are not only regulatory or reputational, but necessary to earn the trust of users who may deposit billions of dollars into their system.

This reality is OK.

Practically speaking, we suspect that transaction filtering will only prevent a subset of exploits, like freezing user funds within a vulnerable smart contract until the project can deploy a fix. Direct intervention by network developers will remain reserved for high-impact incidents.

The primary challenge in the coming years will be preventing scope creep where transaction filtering that is implemented to stop heists is later expanded to discriminate against honest users. Credible neutrality is still important, even if policies that advocate for developer intervention to protect user funds is prioritised from time to time.

If nothing else, users will at least save on fees from failed transactions, a significant UX improvement.